Filter

Contents

What Are Call Options And How Do They Work?

Contents

WHAT IS A CALL OPTION?

A call option is a derivative contract that gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to be long 100 shares of an underlying asset at a certain price (called the strike price) on or before the expiration date. If the asset’s price goes up, the value of the call contract also increases. Conversely, if it goes down, the value of the call option decreases.

To secure the right to buy the underlying, a premium is paid to the seller of the call contract. Buyers of call options can let the option expire if the stock price stays below the strike price or sell the contract prior to expiration at the market value to recoup losses. If the stock price rises well above the call contract, the buyer has the right to exercise the trade and obtain 100 shares of stock, where the counterparty would be assigned – in this instance the counterparty is obligated to sell 100 shares of stock to the call contract owner.

The three main characteristics of an options contract are:

- Strike price: the agreed-upon price at which the underlying asset, 100 shares of stock, will be exchanged

- Expiration date: the date at which the contract is settled or expires worthless

- Premium: the amount that the buyer pays or the seller collects for a single contract

PROFIT/LOSS CHARTS

Long Call Options

OTM |  ITM |

Short Call Options

OTM |  ITM |

HOW DO CALL OPTIONS WORK?

Call options work by having two parties, a buyer and a seller, exchange an underlying at an agreed-upon price, on or before the expiration date. Traders typically buy call options when they expect an underlying's price to increase significantly in the near future, but don’t have enough money to buy it or want to limit their monetary risk compared to buying 100 shares outright. They also commonly buy call options if they think that implied volatility (IV) will increase before the option expires.

There are two alternatives to exercising the option: the buyer can choose to either sell the contract before expiration, which is more popular than exercising, or let it expire worthless and forego only the premium paid up front to buy the call contract if the stock price remains below the call strike price.

Since the call only has value at expiration if the stock price is above the strike price, the call seller wants the stock price to remain below the strike price. This allows call sellers to keep the premium collected up front for selling the contract and avoid having to fulfill their contractual obligation. Remember, a call contract gives the owner the right to buy 100 shares at a certain strike price. So, if the stock never reaches that level, the contract owner can just buy 100 shares at the lower market price instead of exercising the call contract.

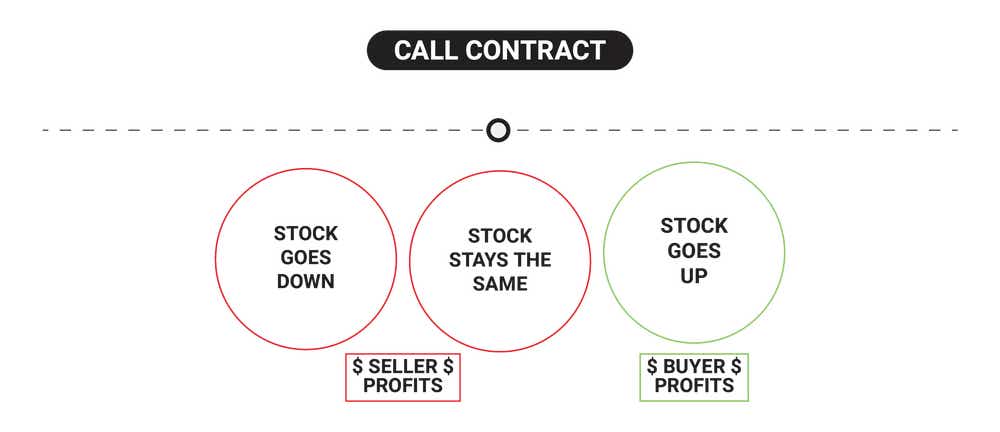

The buyer and the seller of the options contract have opposite assumptions in the contract.

LONG CALL (BULLISH)

The call buyer wants the stock price to increase well above the call strike price by the expiration of the contract so they can purchase 100 shares of stock at a discount relative to the market price or sell the call contract for more than what they paid for it. If the strike is below the stock price, the call is said to be in-the-money (ITM), which just means it has real value to the owner at expiration.

Short Call (Bearish)

The call seller wants the stock price to remain below the call strike price, so they can keep the premium collected up front for selling the call, which then turns to profit when the call contract expires worthless. If this is the case, the call is said to be out-of-the-money (OTM), since it wouldn’t have value to the call owner at expiration.

Implied Volatility in Long Calls

Some traders believe that it's best to place long calls, or long call spreads, in underlyings with low implied volatility (IV) rank and/or low IV because the debit paid – the price paid for the option or spread – will be less for underlyings with a low IV rank as opposed to a high IV rank. As IV increases, the market is indicating a greater expected range of movement in the underlying. Therefore, option sellers demand a higher premium because underlyings with a high IV are perceived to have a greater potential for large stock price moves, compared to low IV underlyings.

BUYING A CALL OPTION (LONG CALL)

Buying a long call typically represents a bullish assumption of the market or underlying. So, long call options are traded when an investor expects the underlying's price to have a significant move upwards, past their long call strike by the expiration of the contract. Ideally, the call is deep ITM well before, or at the expiration of the contract. If the price of the option exceeds the cost of purchasing it upfront, the call buyer would profit.

Long Call Example

Suppose you think that the share price of XYZ is going to increase quite a bit because of a new product roll-out. It’s currently trading at $2,800, and you’d like to invest in the company, but you don’t have enough buying power to buy 100 shares of the stock outright.

Buying one call option contract enables you to control the theoretical equivalent of 100 shares of stock at your strike price, without owning the shares outright, at a much lower entry price. At the current market price, buying 100 shares of XYZ would leave you with $280,000 in risk, but you can get exposure to the same number of shares for much less through a long call option.

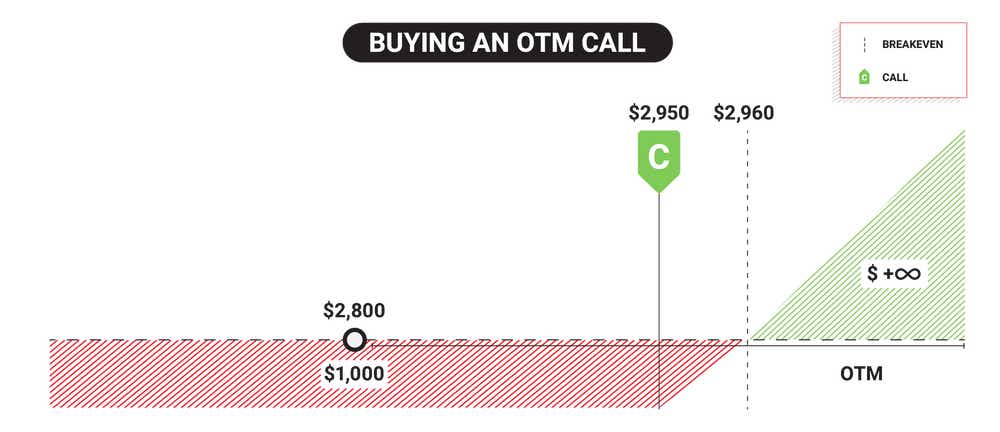

Let’s say you buy an XYZ stock call option at a premium – or debit paid – of $10 per share ($1,000 in real dollar terms), at a strike price of $2,950 and an expiration date of 30 days. If the stock price goes up, and trades above the strike price before the expiration date, you can sell the call option and make a profit.

Even if the stock doesn’t rise above $2,950, the call options can still increase in value substantially if there’s a swift bullish move with plenty of time left until expiration. With a sharp increase that moves the stock price past the call strike or just closer to the call strike, you can sell the call option for a profit if it is trading for more than what you bought it for.

Since you don’t have enough buying power to exercise the option, you close the trade by selling the contract at a higher premium – as long as the call contract is worth more than $10 at any point in your trade, you’d realize a profit if you closed the contract. The profit would be the difference between the debit of $10 you paid to own the call, and the higher credit you receive for selling the contract to close the trade. For example, the premium to sell was $25 after a rally in XYZ; compared to the $10 you paid to buy the contract, you’d make a profit of $15 per share – which adds up to $1,500 since you’re controlling the theoretical equivalent of 100 shares of stock.

On the other hand, if the stock price isn’t above the $2,950 strike price by the expiration date, the option would expire worthless (if you didn’t sell it beforehand) and you’d lose only the $1,000 premium you paid initially to control the equivalent of 100 shares at your strike price.

WHEN TO CLOSE A LONG CALL OPTION

Buyers of long calls can sell them at any time before expiration for a profit or loss, but ideally the trade is closed for a profit when the value of the call exceeds the entry price for purchasing it. This can happen when the stock price rises well above the call contract, or if there is a swift move in the stock price well before expiration. There is unlimited profit potential in a call option because there is no limit to how high a stock price can go.

Long call options can be closed in one of three ways:

In all these instances, the profit or loss made depends on the price of the underlying at the time of the exit transaction (or expiry in the first case). If the call buyer opts for the third option above, they’d convert their call option into 100 shares of stock, so the risk would still be on the table, and they would give up any extrinsic value remaining in the long call option. This is why assignment is generally rare, and option 1 and 2 are much more popular.

Unlike the first two examples of closing a long call, exercising the option and turning the call into 100 shares of stock is subject to having enough capital to buy and hold the underlying shares.

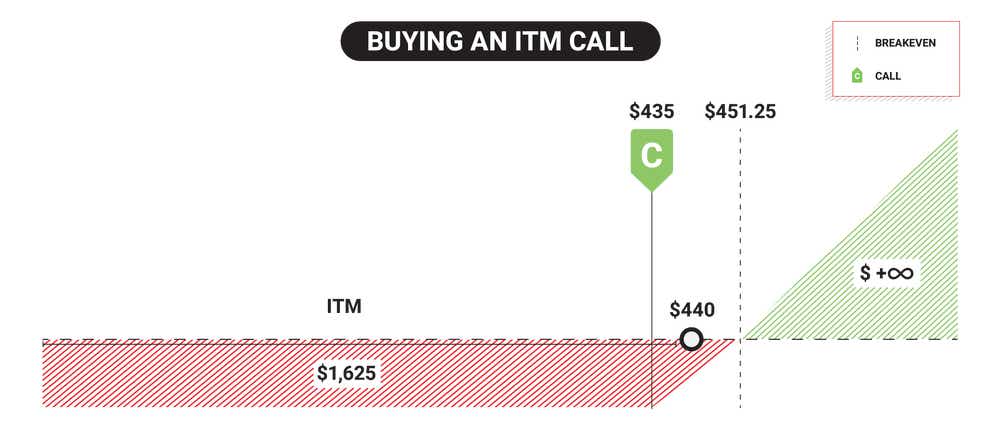

Let’s look at how profitability can be determined. A long call can be purchased either ITM or OTM, which contributes to the upfront cost to buy the option, as well as the potential profit or loss at expiration.

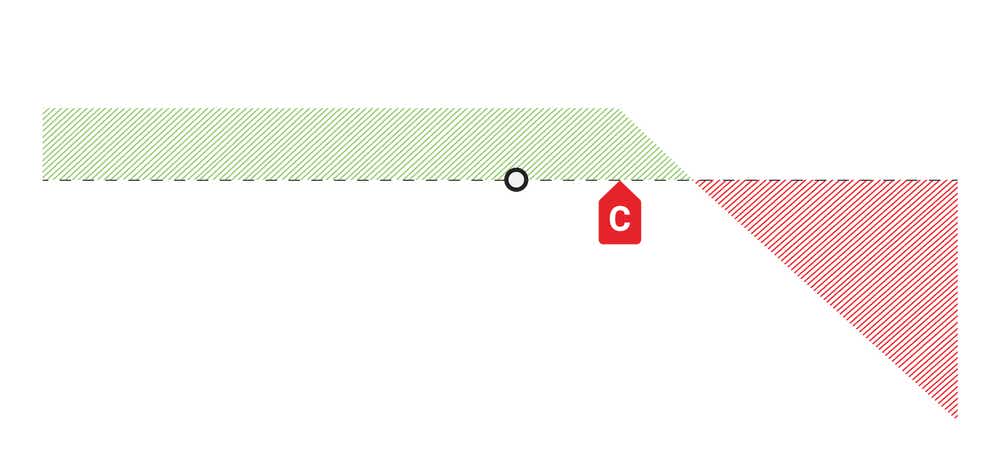

IN-THE-MONEY (ITM)

Here’s an example of buying a call option that’s ITM. With stock ZYX trading at $440, buying an ITM call option would be any strike below $440. In this instance, let’s buy the $435 ITM call option.

To figure out at which price this trade will be profitable, you add together the strike price of the option ($435) and the debit paid ($16.25); which adds up to $451.25. This total represents the long call's breakeven price. The long call becomes profitable if the stock price rises above the breakeven point.

Since you are paying for the right to control 100 shares of theoretical stock up front, the call’s intrinsic value must be at the breakeven point (where the red loss zone meets green profit zone in the image above) at expiration to yield no loss or profit.

Out-Of-The-Money (OTM)

A variation of the ITM call option example is an OTM long call option, which works the same way. Only now, the trade does not start with intrinsic value, and there won’t be real value for the contract owner if the stock trades below the strike price at expiration. Prior to expiration, the contract owner can also choose to close the trade by selling the call option at market value, and their P/L will be dependent on whether their closing price is higher or lower than their entry price (either ITM or OTM).

It’s important to note that when markets project more stock price movement, options prices can increase, which drives implied volatility (IV) higher. There are many factors that contribute to an options price including time to expiration, how close the option is to the stock price, and whether that option is ITM or not.

EXERCISING A CALL OPTION

Exercising a call option refers to the buyer acting on their right to convert their option into 100 shares of stock. This is rare though, as converting an option to stock means burning the extrinsic value remaining on the option itself. Selling the option and then just buying the shares at market price typically yields a better or similar result, since you can sell the extrinsic value back to the market in this case.

On the other hand, options sellers are not automatically assigned stock if the option they’re short moves ITM – extrinsic value plays a big role in preventing assignment, so if there is plenty of extrinsic value in an ITM short option, assignment risk is typically low (excluding dividend risk, which changes things to a degree).

Extrinsic value is simply any value over the intrinsic value of the option. For example, if a stock is trading at $100 and there is a $90 strike call trading for $12.50, we know that the intrinsic value is $10 since it's $10 ITM, and the extrinsic value would be $2.50. This option isn’t likely to be exercised by the owner (and assigned to the short party) because they would be giving up $250 dollars. Instead, they may sell the option back to the market to retain that, which means the short option holder would still be short the option.

WHEN A LONG CALL OPTION WILL LOSE MONEY

A long call option will lose money at expiration if the price of the stock doesn’t move above the breakeven price, which is the strike price plus the debit paid. So, in the example above, the long call loses money if the stock price ends up below the breakeven price of $2,960 ($2,950 + $10).

If the stock price is between the strike price ($2,950) and the breakeven price ($2,960), the trade will lose between $0.01 and the premium paid, which in this case would be $10 per share of stock. Since one call option controls 100 shares of stock, the amount for one share will be a hundredfold.

The trade will be at maximum loss if it expires at or below the strike price. Prior to expiration, the call will hold some sort of value, but the further OTM it is from the stock price, the less extrinsic value it will hold.

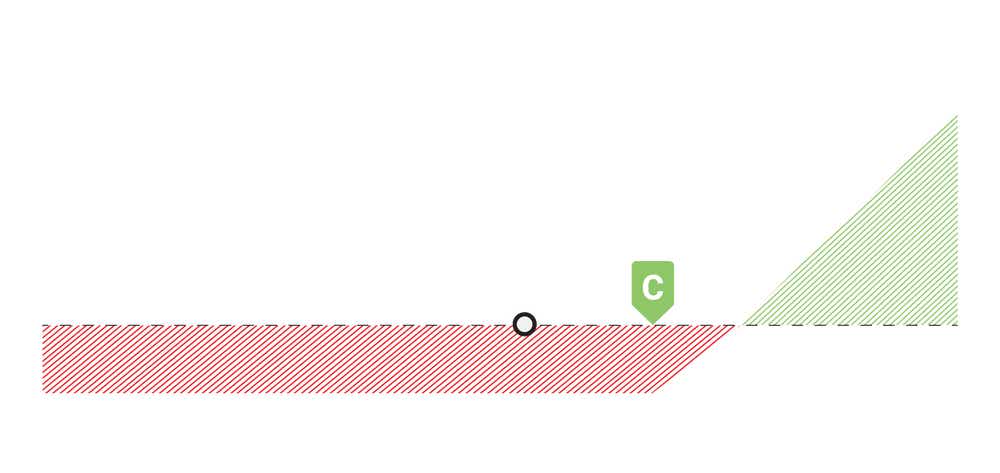

SELLING A CALL OPTION (SHORT CALL)

Selling a call option to open a trade means taking the other side of a long call transaction - selling to open (short call) instead of buying to open (long call). For every long call, there’s a short one – together, these form a contract that stipulates the agreement to exchange the underlying at a predetermined price by the expiration date.

Contrary to long calls, the market assumption in a short call position is typically bearish. Sellers of call options either expect the underlying’s market price to drop or remain neutral. As long as the option remains OTM or above the stock price at expiration, the seller gets to keep the premium received without having to exchange the underlying.

As stated above, being short a call option doesn’t mean you’re automatically short 100 shares of stock if the stock price rises above the short call. As long as there’s substantial extrinsic value remaining in the option, assignment risk is low, since the call buyer would be giving that value up to obtain the shares (which doesn’t make sense in most cases outside of collecting a dividend payment).

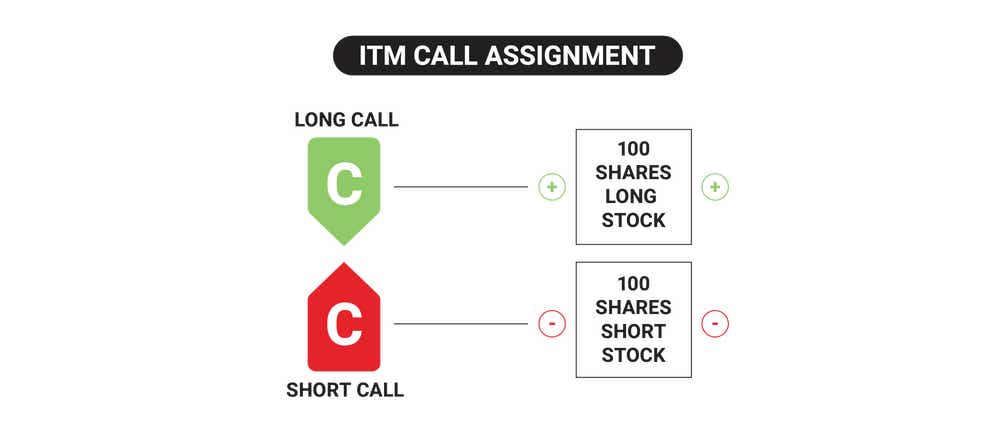

SHORT CALL OPTION ASSIGNMENT

If a long call buyer exercises their right to convert the call to 100 shares of the underlying, the seller is obligated, through assignment, to make the exchange. In this case, the seller typically incurs a loss, as buyers usually exercise a long call that has already moved ITM, but the short call holder would still have 100 short shares as an active trade.

SHORT CALL EXAMPLE

Imagine you are the seller in the long call example.

Despite XYZ rolling out a new product, you don’t think that the share price of $2,800 will rise. In fact, you’re expecting a pullback, especially since the launch of the new product is being met with a lot of criticism, with questions about usefulness and practicality.

You attempt to capitalize on the skepticism around the product release, shorting one call option at a strike price of $2950.00. You collect a premium of $10 per share for selling the call, which adds up to $1,000 in real dollar terms since you assume 100 shares of short stock risk when selling a call.

After some initial movement in both directions, the stock ends up trading below the strike price of $2,950 by the expiration date of your contract. Since this results in the option expiring OTM and worthless, you realize a profit of $1,000, the premium received from assuming the risk of 100 short shares above $2950. This amount excludes any additional costs such as commission and regulatory fees.

Prior to expiration, options will still fluctuate in value as the market moves. Even if the stock doesn’t reach $2950 in this case, you may still see an unrealized loss, if the option is trading for more than $10.00 which is what you sold it for.

Let’s assume the day after you sold the option, the stock rallied from $2800 to $2850. Maybe your option is now worth $12.00, which would mean you’d see an unrealized loss of $200, even though the option would still be worthless at expiration as it’s OTM. Keep this in mind with short and long options trades.

At expiration, the result of short options trading is pretty binary – you either keep the credit received from selling the option if it expires OTM and realize that as profit, or if the strike is ITM at expiration the option will be worth the equivalent of how far ITM it is.

For example, if the stock is at $2965 in this example, it would be worth $15.00 or $1500 in real dollar terms since the option would be $15 points ITM. You collected $10.00 upfront though, so the realized loss from closing the position would be $5 or $500 in real dollar terms.

If you did not close the position and let it expire ITM, the short call would convert to 100 short shares of stock at $2950 and you would still keep the premium received up front.

To avoid assignment or taking shares at expiration, you can roll the short call further out in time, or close the contract to end the trade.

As a long option holder, you need the stock price to rise above the strike by more than what you paid for the option to realize a profit.

With short options trades, you can absorb movement above your strike, equivalent to the credit received from selling the option before you reach your breakeven price.

CALL OPTION VS PUT OPTIONS: WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENCES

There are two types of options: calls and puts. These can be utilized individually, or as part of options strategies such as vertical spreads and iron condors.

Understanding the differences between calls and puts is fundamental in paving the way for more complex strategies. Some of the key differences are listed below:

Call Options

- The contract owner gets the right, but not the obligation to buy the underlying

- The buyer is bullish (long call), the seller is bearish (short call)

- Long calls can profit when the stock price increases past the strike; and/or IV increases without a stock price sell-of

- Short calls can profit when the stock price decreases, goes up a little, but not past the strike, or it doesn’t move; and/or IV decreases; and/or time passes – as long as the contract expires OTM and worthless, the short call seller realizes max profit equivalent to the credit received up front.

Put Options

- The contract owner has a right, but not the obligation to sell/short the underlying at their strike price

- The buyer is bearish (long put), the seller is bullish (short put)

- Long puts can profit when the stock price decreases past the put strike; and/or IV increases, especially when combined with a stock price sell-off

- Short puts can profit when the stock price increases, it goes down a little, but not past the strike, or it doesn’t move; and/or IV decreases; and/or time passes – as long as the put contract expires OTM and worthless, the short put seller realizes max profit equivalent to the credit received up front

BUYING A CALL OPTION VS BUYING STOCK

There are several differences between buying call options and buying stock. Below are some of the key ones.

Call Options

- Can control 100 shares of an asset, including stocks, at a price higher or lower than the market price

- Closing the trade can happen three ways, and is tied to an expiration date

- Greater flexibility through variables such as strike price, expiration and strategies

- The maximum loss is the premium paid (subject to trade management) – this excludes any additional fees

Stocks

- Can be bought outright at the market price

- The only way to close a pure stock position is by selling the shares; shares can belong to you in perpetuity

- Less flexibility

- The maximum loss is equivalent to the share price going to $0 (excluding any additional fees)

Call Options Summed Up

- Are typically utilized by traders with a bullish market assumption

- Are derivative contracts – an agreement between two parties, a buyer and a seller

- Give the buyer the right, but not an obligation, to exercise their right to own 100 shares of stock at the strike price; while sellers are obligated to sell 100 shares in the case of an assignment

- Consist of three main characteristics: strike price, expiration date and premium

- Work by having an underlying exchanged at a predetermined strike price, by the expiration date if the call is ITM

- Can be closed in three different ways: letting them expire worthless, selling the contract, or exercising the call

- Differ from the other type of options contracts, puts, in several ways

FAQs

What is a call option and how does it work?

A call option is a contract between two parties, a buyer and a seller, to exchange a specified underlying asset at a predetermined price by a certain expiration date. Based on the stock price movement in relation to the strike price and other factors, either the buyer or the seller eventually makes a profit, whereas the other party would incur a loss.

Call option buyers profit when the stock price rises well past their strike price ITM before or at the expiration of their contract.

On the other hand, call option sellers profit when the option expires worthless or OTM at expiration.

Explore what defines a call option and learn how call options work

Why should I buy a call option?

When a trader buys a call option, they believe that there’s potential to profit with a stock price increasing rapidly past the strike price chosen before the expiration of the contract. However, regardless of how likely your prediction may seem to prove to be true, it’s still not a guarantee. Just like with any other trading activity, there are risks in trading call options.

What happens when I sell a call option?

Selling a call option is a bearish position. Ideally, traders who sell calls want the underlying’s price to drop and for the option to expire OTM. Short call positions can also be bought to possibly lock in a certain profit or loss before expiration.

Can I sell a call option early?

Yes – call option buyers can close the position at any time by selling the contract for the market value. This is a popular choice, as many traders just speculate on the call option price itself, rather than converting the call option into shares of stock.

On the same note – short call sellers can also close their position prior to expiration by purchasing the option back from the market.

Option buyers buy the contract to open and sell the contract to close; whereas option sellers sell the contract to open and buy the contract to close.

tastylive content is created, produced, and provided solely by tastylive, Inc. (“tastylive”) and is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be, trading or investment advice or a recommendation that any security, futures contract, digital asset, other product, transaction, or investment strategy is suitable for any person. Trading securities, futures products, and digital assets involve risk and may result in a loss greater than the original amount invested. tastylive, through its content, financial programming or otherwise, does not provide investment or financial advice or make investment recommendations. Investment information provided may not be appropriate for all investors and is provided without respect to individual investor financial sophistication, financial situation, investing time horizon or risk tolerance. tastylive is not in the business of transacting securities trades, nor does it direct client commodity accounts or give commodity trading advice tailored to any particular client’s situation or investment objectives. Supporting documentation for any claims (including claims made on behalf of options programs), comparisons, statistics, or other technical data, if applicable, will be supplied upon request. tastylive is not a licensed financial adviser, registered investment adviser, or a registered broker-dealer. Options, futures, and futures options are not suitable for all investors. Prior to trading securities, options, futures, or futures options, please read the applicable risk disclosures, including, but not limited to, the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options Disclosure and the Futures and Exchange-Traded Options Risk Disclosure found on tastytrade.com/disclosures.

tastytrade, Inc. ("tastytrade”) is a registered broker-dealer and member of FINRA, NFA, and SIPC. tastytrade was previously known as tastyworks, Inc. (“tastyworks”). tastytrade offers self-directed brokerage accounts to its customers. tastytrade does not give financial or trading advice, nor does it make investment recommendations. You alone are responsible for making your investment and trading decisions and for evaluating the merits and risks associated with the use of tastytrade’s systems, services or products. tastytrade is a wholly-owned subsidiary of tastylive, Inc.

tastytrade has entered into a Marketing Agreement with tastylive (“Marketing Agent”) whereby tastytrade pays compensation to Marketing Agent to recommend tastytrade’s brokerage services. The existence of this Marketing Agreement should not be deemed as an endorsement or recommendation of Marketing Agent by tastytrade. tastytrade and Marketing Agent are separate entities with their own products and services. tastylive is the parent company of tastytrade.

tastyfx, LLC (“tastyfx”) is a Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) registered Retail Foreign Exchange Dealer (RFED) and Introducing Broker (IB) and Forex Dealer Member (FDM) of the National Futures Association (“NFA”) (NFA ID 0509630). Leveraged trading in foreign currency or off-exchange products on margin carries significant risk and may not be suitable for all investors. We advise you to carefully consider whether trading is appropriate for you based on your personal circumstances as you may lose more than you invest.

tastycrypto is provided solely by tasty Software Solutions, LLC. tasty Software Solutions, LLC is a separate but affiliate company of tastylive, Inc. Neither tastylive nor any of its affiliates are responsible for the products or services provided by tasty Software Solutions, LLC. Cryptocurrency trading is not suitable for all investors due to the number of risks involved. The value of any cryptocurrency, including digital assets pegged to fiat currency, commodities, or any other asset, may go to zero.

© copyright 2013 - 2026 tastylive, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Applicable portions of the Terms of Use on tastylive.com apply. Reproduction, adaptation, distribution, public display, exhibition for profit, or storage in any electronic storage media in whole or in part is prohibited under penalty of law, provided that you may download tastylive’s podcasts as necessary to view for personal use. tastylive was previously known as tastytrade, Inc. tastylive is a trademark/servicemark owned by tastylive, Inc.

Your privacy choices