Filter

Contents

Strangle Options Strategy: How Long and Short Strangles Work

Contents

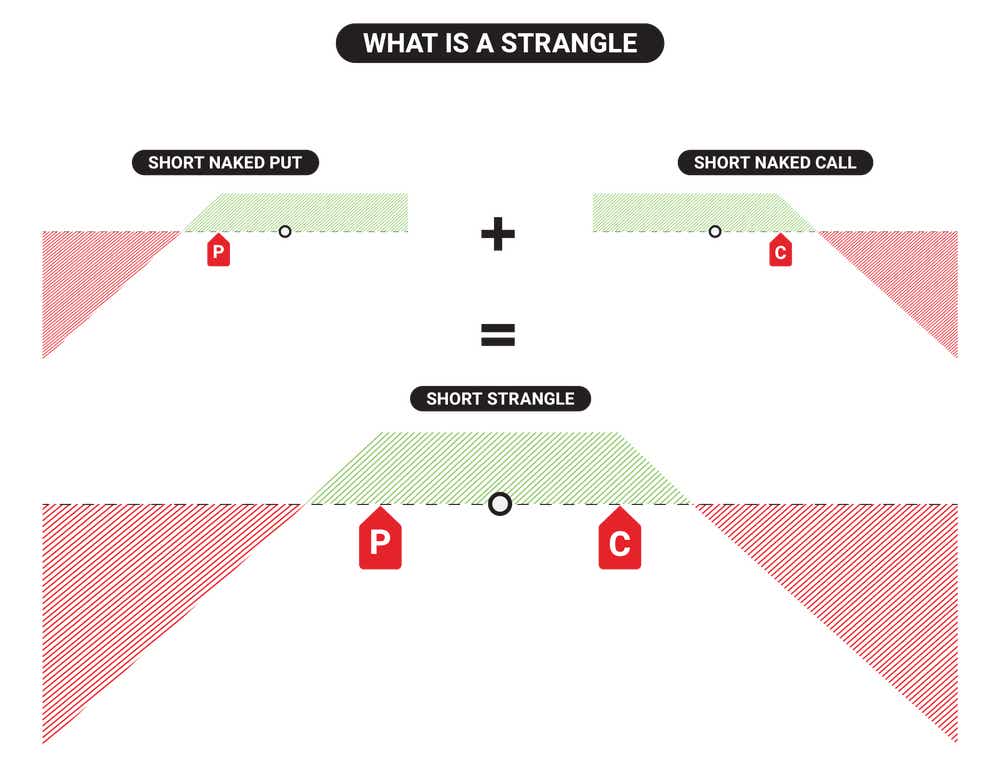

What is a Strangle?

A strangle is an options strategy that is deployed using an out-of-the-money (OTM) call and put with different strike prices in the same expiration cycle.

When both the call and put are sold, the resulting position is known as a short strangle. The best case scenario with a short strangle is realized if both options expire worthless, where the credit received up for selling the two options becomes max profit.

When both the call and the put are purchased, the resulting position is known as a long strangle. The best case scenario with a long strangle is if the stock price moves well past one of the strikes, either to the upside or downside. The position can then be sold for more than the trader purchased the strangle for upfront, resulting in variable profit.

Long Strangle Strategy: Overview and Setup

(Both options are typically in the same expiration)

A long strangle is a defined risk position because the maximum loss is represented by the total amount of premium paid to purchase the call and the put. Since both options are directionally opposite, one side will typically lose money when the other is profitable.

Long strangles can be profitable prior to expiration without a move in-the-money (ITM), but every day that passes where the stock price move is minimal, both options may see a reduction in extrinsic value premium.

For a long strangle to be profitable at expiration, the stock needs to be past one of the strikes by more than the debit paid up front for both strikes. This is why a long strangle is a low probability trade if held to expiration.

Long Strangle Profit/Loss Chart

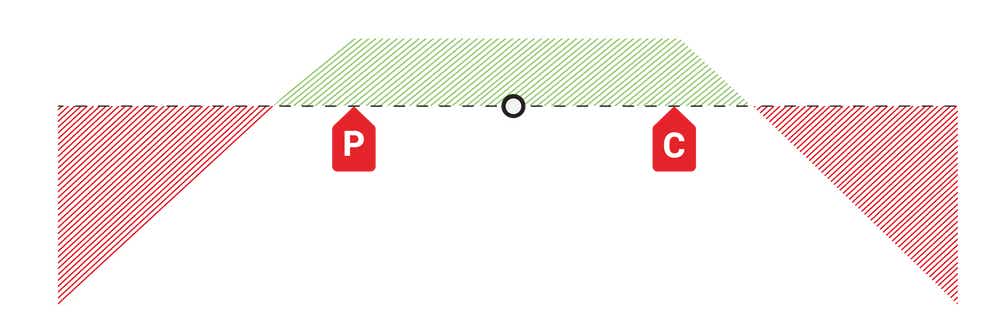

Short Strangle Strategy: Overview and Setup

(Both options are typically in the same expiration)

A short strangle is an undefined risk position because the maximum loss is undefined on the call side - with both options, you are obligated to assume the risk of 100 shares of long stock below the short put, and 100 shares of short stock above the short call. A short put cannot realize losses more than the stock reaching $0.

Just like a long strangle, both options will typically move against each other in terms of profitability in the short-term. On directional moves in the stock, one option may lose value while the other gains value against you.

Short strangles can be profitable prior to expiration if enough time passes with little movement in the stock price, or there is a big implied volatility contraction. A combination of both is also beneficial to the short strangle trader, since extrinsic value decay is a benefit to the short strangle strategy.

For a short strangle to be profitable at expiration, the stock just needs to be between the short option strikes - this results in the options expiring worthless, and the max profit realized, which is equivalent to the premium collected upfront for selling both options.

Short Strangle Profit/Loss Chart

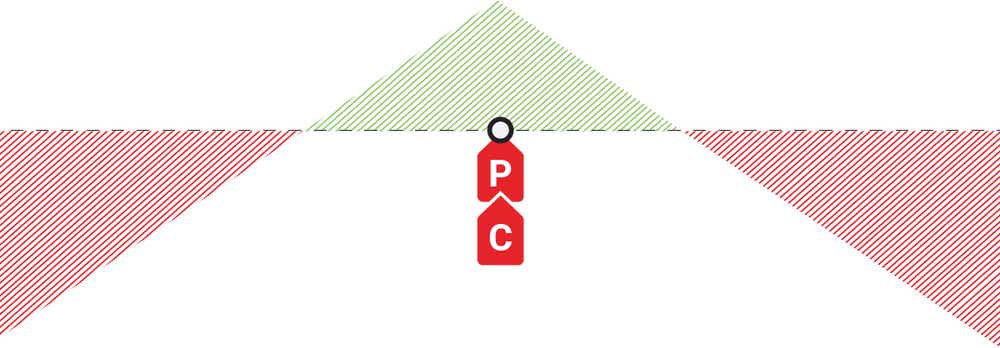

Strangle vs Straddle: What Are the Differences?

The straddle and strangle are similar strategies, and therefore share similar risk characteristics.

The primary difference between a straddle and strangle is that a straddle is constructed using at-the-money (ATM) options, whereas the strangle is constructed using out-the-money (OTM) options. Both strategies involve a call and put from the same expiration cycle.

For example, if hypothetical stock ABC is trading for $10, one could deploy a short strangle by selling the $12-strike call and the $8-strike put from the same expiration cycle. A short straddle, on the other hand, would be deployed by selling the $10-strike call and the $10-strike put.

Short strangles and short straddles are undefined risk positions because the maximum potential loss isn’t defined prior to trade deployment. Long strangles and long straddles are defined risk positions because the maximum potential loss is defined prior to trade deployment—in either case the maximum loss is the total premium paid to purchase both options.

Short Strangle Profit/Loss Chart

Straddle Profit/Loss Chart

How a Strangle Works in Options Trading

A short strangle is a position that profits when the underlying stock stays between the short strikes as time passes, or from a decrease in implied volatility. The maximum potential profit is equivalent to the total premium received for selling the two options, less any trading costs. The maximum potential loss is undefined, as you assume the risk of +100 or -100 shares of stock on either side of the market beyond your strikes.

Alternatively, a long strangle is a position that profits at expiration when the underlying stock breaks through the strike price of the call or put, or from an increase in implied volatility or swift move towards one of the strikes prior to expiration. The maximum potential profit is undefined, however, the maximum potential loss is the total premium outlaid to initiate the position.

Calculating Breakevens for a Long Strangle

A long strangle is a long volatility strategy. It is used when a trader expects the underlying to make a big move, but is unsure about the direction. A long strangle may also be deployed when a trader believes that future realized volatility will be greater than the current implied volatility priced in the options. It has limited risk and unlimited profit potential.

In order to breakeven on a long strangle at expiration, the underlying stock price must rise above the call strike price, or decrease below the put strike price. The underlying stock price must move beyond the strike price of the call or put by the same amount of total premium that was outlaid to enter the position.

The position profits if the underlying stock moves beyond those breakeven points at expiration. Prior to expiration, the position profits if there is a swift move in either direction and the trader can sell the strangle for more than they purchased it for.

Calculating Breakevens for a Short Strangle

A short strangle is a short volatility strategy. It is used when a trader expects minimal movement in the underlying price, or when a trader expects future realized volatility to be less than the current implied volatility priced in the options. It has unlimited risk and limited upside.

To breakeven on a short strangle, the underlying stock price cannot move beyond the strike prices of the call and put by more than than the total amount of premium collected from selling both options.

The position profits at expiration if the underlying stock price remains within the breakeven points.

The two breakeven points for a short strangle can be calculated using the following formulas:

- Upper Breakeven Point = Strike Price of Short Call + Net Premium Collected

- Lower Breakeven Point = Strike Price of Short Put - Net Premium Collected

With a short strangle you are betting against the movement of the underlying stock. With a long strangle, you are betting for the movement of the underlying stock.

tastylive approach

With strangles, it is important to remember that we are working with truly undefined risk in selling a naked call. We focus on probabilities at trade entry, and make sure to keep our risk / reward relationship at a reasonable level.

Implied volatility (IV) plays a huge role in our strike selection with strangles. The higher the IV, the wider our strangle can be while still collecting similar credit to a strangle with closer strikes that is sold in a lower IV environment. If we choose to keep our strikes closer to the stock price, a higher IV environment will yield a much larger credit, as IV is essentially a reflection of the option prices.

Our target timeframe for selling strangles is around 45 days to expiration. Our studies show this is a great balance between shorter and longer timeframes.

CLOSE / MANAGE

WHEN TO CLOSE

The first profit target is generally 50% of the maximum profit. This is done by buying the strangle back for 50% of the credit received at order entry.

WHEN TO MANAGE

With premium selling strategies, defensive tactics revolve around collecting more premium to improve our breakeven price, and further reduce our cost basis. With short strangles specifically, we have shown through our studies that rolling the untested side (non-losing side) closer to the stock price when our tested side (losing side) is breached is optimal.

Long Strangle Example

Imagine stock XYZ is trading for $100/share. A trader has decided to purchase a long strangle in XYZ, because they are expecting a large move to materialize in the stock prior to the expiration of the options.

For the purposes of this example, imagine that the current month is April, and that the trader is planning to use the May expiration cycle to deploy this long strangle. Furthermore, the trader has elected to use the $105-strike call and the $95-strike put to construct the strangle.

Currently, the $105-strike call is trading for $4, while the $95-strike call is trading for $3. That means that to enter the position, the trader would need to pay a total of $7 ($4 + $3 = $7) in premium.

To calculate the associated breakeven points for this position, one can use the following formulas:

- Upper Breakeven Point = Strike Price of Long Call + Net Premium Paid

- $105 + $7 = $112

- Lower Breakeven Point = Strike Price of Long Put - Net Premium Paid

- $95 - $7 = $88

Taken together, the trader would need stock XYZ to rally to $112

by the expiration of the contracts to breakeven on this hypothetical position. And XYZ would need to rally above $112 for the trader to make a profit on the position.

Alternatively, stock XYZ could also drop to $88, and the trader would also breakeven on the position at expiration. To produce a profit to the downside, stock XYZ would need to drop lower than $88.

The maximum potential loss from this hypothetical long strangle is the total amount of premium outlaid to enter the position, and that is realized if the stock price is between the strikes at expiration. The maximum potential profit is theoretically unlimited, as there is no limit to how high a stock price can go.

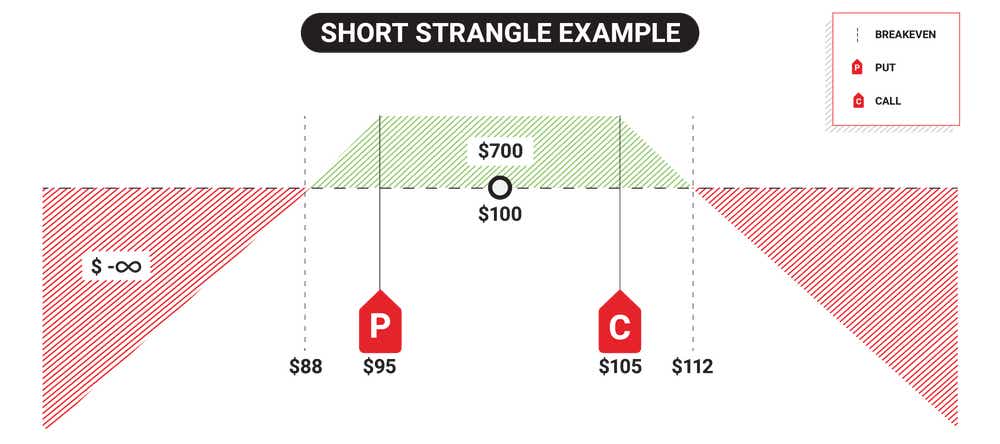

Short Strangle Example

Looking at the reverse situation, imagine another trader in the market has decided to take the opposite side of this position — to sell a short strangle.

In this hypothetical example, they would therefore need to sell both of the aforementioned options.

With the $105-strike call trading for $4, and the $95-strike put trading for $3, that means that when executing this short strangle the trader would receive a total of $7 ($4 + $3 = $7) in premium.

The breakevens for the short strangle are therefore exactly the same as for the long strangle. But to make a profit on the position, stock XYZ needs to trade somewhere between those two breakeven points, as opposed to beyond them.

- Upper Breakeven Point = Strike Price of Short Call + Net Premium Collected

- $105 + $7 = $112

- Lower Breakeven Point = Strike Price of Short Put - Net Premium Collected

- $95 - $7 = $88

Taken together, the above means that stock XYZ would need to trade between $88 and $112 to at least breakeven on the position at expiration.

The optimal result would be for stock XYZ to trade between $95 and $105, because that would allow the short strangle holder to collect the maximum amount of profit from the premium sold up front for entering the position.

The maximum potential loss from a short strangle isn’t defined prior to position deployment, as this is an undefined risk position. Undefined risk refers to the risk that is accompanied with naked short options and when your possible max loss is unknown on order entry.Strangle Options Strategy Summed Up

- A strangle is an options trading strategy involving both a call and put option with different strike prices but the same expiration date.

- When both the call and put are purchased, the resulting position is referred to as a long strangle, and the trader wants the stock to move beyond the strikes prior to expiration.

- When both the call and put are sold, the resulting position is referred to as a short strangle, and the trader wants the stock to stay within the strikes at expiration.

- Long strangles typically perform optimally when there’s a big move in the underlying stock, whereas short strangles perform optimally when the underlying sits still or moves sideways.

- The maximum potential loss from a long strangle is the total premium laid out to enter the position, whereas the maximum theoretical loss from a short strangle is undefined

- The strangle strategy is very similar to the straddle strategy, except that the straddle position is constructed using at-the-money (ATM) options, whereas strangles are constructed using out-of-the-money (OTM) options

- Long and short strangles are not typically hedged upon position deployment, because both are theoretically delta neutral. However, the position holder might elect to hedge a long or short strangle if the underlying stock makes a big move in either direction.

FAQs

What is a strangle in trading?

A strangle is a neutral options strategy that combines a call and put option with different strike prices and the same expiration date.

How does a strangle make money?

A long strangle is profitable when the price of the underlying moves sharply in either direction prior to expiration, to a point where the trader can sell the strangle for more than what they bought it for up front.

A short strangle is profitable if the price of the underlying remains within the strike prices at expiration, where the trader keeps the credit received up front for selling the strangle.

Why would I buy a long strangle?

A long strangle is a profitable strategy if you think that the price of the underlying will experience a big change prior to the expiration of your contracts, but you are not sure of the direction. If this happens, it may offer the long strangle owner the ability to sell the position for more than what they purchased it for up front.

How do I hedge a long strangle?

At deployment, long and short strangles are not typically hedged with underlying stock because the position is theoretically delta neutral, much like a long or short straddle. However, if the underlying stock makes a big move in either direction, the strangle buyer/seller might then decide to hedge the position, or close the position — depending on one’s outlook and risk profile.

An example of hedging a strangle may include selling a put or call (or both) further OTM than the similar option type to reduce the overall cost of the strangle itself, which reduces the max loss in exchange for capping the profit potential on that side.

What role does implied volatility (IV) play in strangles?

As with any options-focused position, implied volatility (IV) can play a big role when trading strangles. In general, traders seek to sell strangles when implied volatility is high and there is an expectation that the underlying stock will sit still or move sideways, which could result in a contraction in the options prices and IV. High implied volatility also translates to higher credits received from the sale of the options, or the ability to get further away from the stock price with the strikes, which is usually attractive to options sellers.

On the other hand, when implied volatility is low, traders may elect to purchase a long strangle, to bet on the stock moving to a greater degree than the current implied volatility. This approach is especially attractive when one expects implied volatility to increase, or when one expects that the underlying stock will make a big move in either direction.

SUPPLEMENTAL CONTENT

Episodes on Strangle

No episodes available at this time. Check back later!

tastylive content is created, produced, and provided solely by tastylive, Inc. (“tastylive”) and is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be, trading or investment advice or a recommendation that any security, futures contract, digital asset, other product, transaction, or investment strategy is suitable for any person. Trading securities, futures products, and digital assets involve risk and may result in a loss greater than the original amount invested. tastylive, through its content, financial programming or otherwise, does not provide investment or financial advice or make investment recommendations. Investment information provided may not be appropriate for all investors and is provided without respect to individual investor financial sophistication, financial situation, investing time horizon or risk tolerance. tastylive is not in the business of transacting securities trades, nor does it direct client commodity accounts or give commodity trading advice tailored to any particular client’s situation or investment objectives. Supporting documentation for any claims (including claims made on behalf of options programs), comparisons, statistics, or other technical data, if applicable, will be supplied upon request. tastylive is not a licensed financial adviser, registered investment adviser, or a registered broker-dealer. Options, futures, and futures options are not suitable for all investors. Prior to trading securities, options, futures, or futures options, please read the applicable risk disclosures, including, but not limited to, the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options Disclosure and the Futures and Exchange-Traded Options Risk Disclosure found on tastytrade.com/disclosures.

tastytrade, Inc. ("tastytrade”) is a registered broker-dealer and member of FINRA, NFA, and SIPC. tastytrade was previously known as tastyworks, Inc. (“tastyworks”). tastytrade offers self-directed brokerage accounts to its customers. tastytrade does not give financial or trading advice, nor does it make investment recommendations. You alone are responsible for making your investment and trading decisions and for evaluating the merits and risks associated with the use of tastytrade’s systems, services or products. tastytrade is a wholly-owned subsidiary of tastylive, Inc.

tastytrade has entered into a Marketing Agreement with tastylive (“Marketing Agent”) whereby tastytrade pays compensation to Marketing Agent to recommend tastytrade’s brokerage services. The existence of this Marketing Agreement should not be deemed as an endorsement or recommendation of Marketing Agent by tastytrade. tastytrade and Marketing Agent are separate entities with their own products and services. tastylive is the parent company of tastytrade.

tastyfx, LLC (“tastyfx”) is a Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) registered Retail Foreign Exchange Dealer (RFED) and Introducing Broker (IB) and Forex Dealer Member (FDM) of the National Futures Association (“NFA”) (NFA ID 0509630). Leveraged trading in foreign currency or off-exchange products on margin carries significant risk and may not be suitable for all investors. We advise you to carefully consider whether trading is appropriate for you based on your personal circumstances as you may lose more than you invest.

tastycrypto is provided solely by tasty Software Solutions, LLC. tasty Software Solutions, LLC is a separate but affiliate company of tastylive, Inc. Neither tastylive nor any of its affiliates are responsible for the products or services provided by tasty Software Solutions, LLC. Cryptocurrency trading is not suitable for all investors due to the number of risks involved. The value of any cryptocurrency, including digital assets pegged to fiat currency, commodities, or any other asset, may go to zero.

© copyright 2013 - 2026 tastylive, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Applicable portions of the Terms of Use on tastylive.com apply. Reproduction, adaptation, distribution, public display, exhibition for profit, or storage in any electronic storage media in whole or in part is prohibited under penalty of law, provided that you may download tastylive’s podcasts as necessary to view for personal use. tastylive was previously known as tastytrade, Inc. tastylive is a trademark/servicemark owned by tastylive, Inc.

Your privacy choices